Five years in, the Advanced Biofuels Process Development Unit has established more than 30 diverse partnerships

Sustainable domestic biomass resources can help reduce the nation’s dependence on foreign oil, generate US jobs, revitalize rural and urban communities, and mitigate the environmental impact of petroleum-based industries.

When the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Advanced Biofuels Process Development Unit (ABPDU) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) was commissioned, the initial focus was on overcoming barriers to biofuel commercialization identified by the DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) Bioenergy Technologies Office (BETO), the primary source of funding for the program.

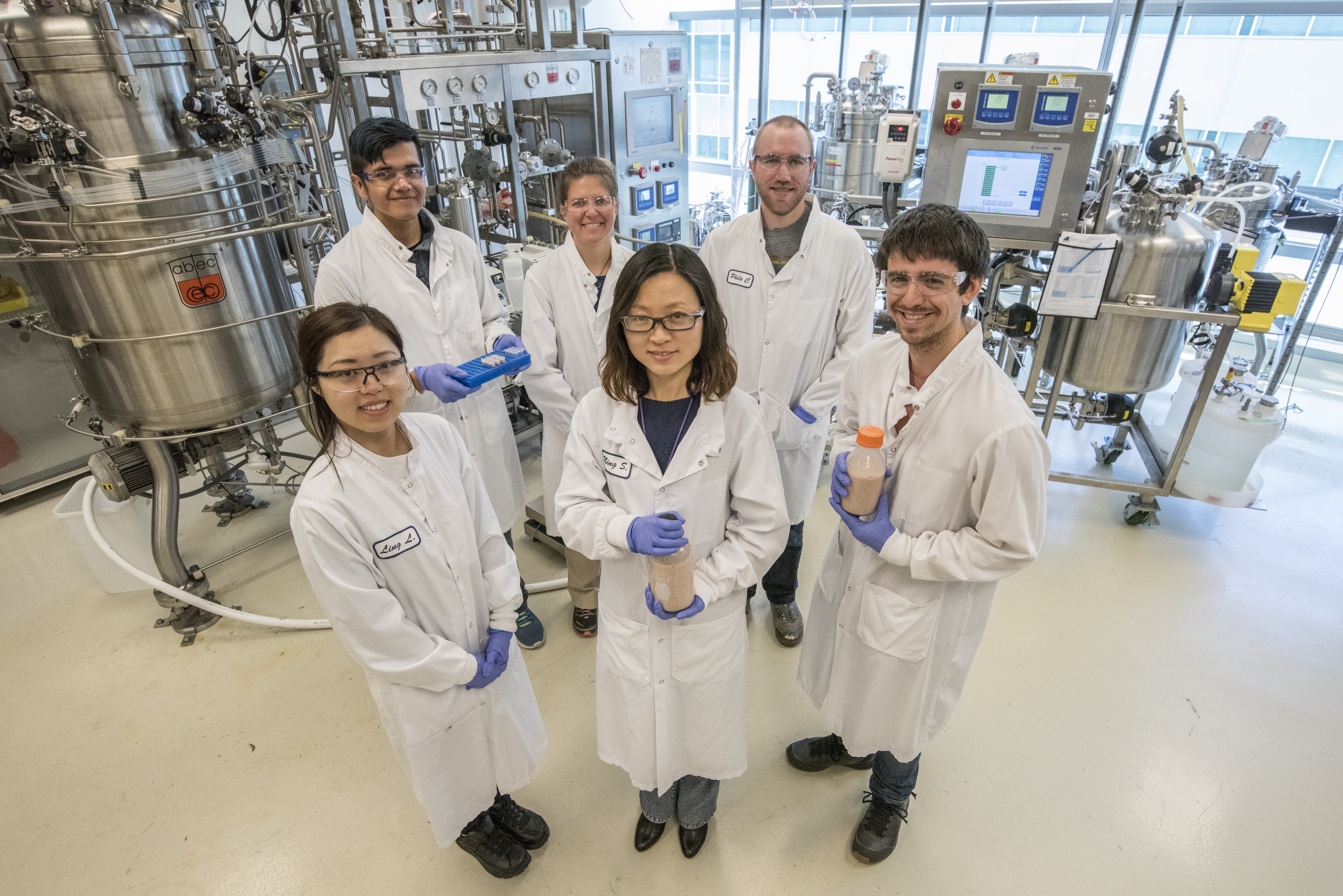

The 15,000 square-foot facility, located in Emeryville, California, was designed to provide bench to pilot scale test beds for advanced cellulosic biofuel technologies developed by partners from other national labs, government agencies, industry, and academia. The ABPDU, which commenced operations in 2012, has capacity for chemical and biomass processing up to 200 liters and fermentation processing up to 300 liters, as well as technology for downstream product recovery, upgrading and purification.

However, in recent years, the scope of the ABPDU’s activities has expanded to encompass a wider range of bio-based material, chemical and protein products. To date, the ABPDU has entered into agreements with more than 30 partners to develop, scale, and validate processes for transforming a variety of nonfood plant-, algae-, and waste-derived materials into a plethora of products. Some of these include: specialty chemicals used in flavorings, fragrances and cosmetics; polymers used in packaging, coatings, and adhesives; enzymes and proteins used in food products; and fibers used in textiles.

“If we’re going to develop a biofuel-based energy economy we need to get all those other molecules we currently get from oil from something else,” explained ABPDU program head Todd Pray. “So this is a way to both develop more efficient manufacturing processes with bio-based inputs, to utilize waste feedstocks—things like garbage and agricultural residue—and to really grow the manufacturing base for the economy.”

What’s more, revenue generated from value added products that can be produced along the pathways from feedstocks to biofuels is a key piece of the economic equation to make next-gen biofuels cost competitive with fossil fuels. Ultimately, Pray believes that the ABPDU, in its role as a shared resource, collaboration hub, and bioprocess incubator, has the potential to catalyze a manufacturing base for the bioeconomy, not just in the biotech hubs around the San Francisco Bay Area or Boston, but in rural and depressed urban areas as well.

“At the ABPDU we have a lot of flexibility both upstream and downstream,” Pray said. “We’re able to utilize pretty much any kind of bio-based feedstock. And we’re not just doing fermentation; we can recover, purify and upgrade different types of products. So it’s not just a protein production facility, not just a biofuel production facility, we can make all of those different molecules downstream of fermentation.”

By leveraging the ABPDU’s capabilities, companies avoid the large cost and long timelines associated with building their own dedicated pilot facilities, allowing them to focus their efforts on product development, later-stage manufacturing facility deployment, and near-term job growth.

The ABPDU and several the companies it has partnered with have been beneficiaries of two “Tech-to-Market” initiatives sponsored by the DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy’s (EERE’s) Bioenergy Technologies Office (BETO): the “Industrial Seedling” laboratory call for proposals pilot, which provided up to $20K per project (up to $40K in its second year) to the national labs to work with pre-seed, seed-stage or early round VC-backed startups; and the Small Business Vouchers (SBV) pilot, which provides small businesses in the clean energy sector with funds ranging from $50K to $300K toward the use of the national labs’ technical resources.

In the “Industrial Seedling” program’s first year, fiscal year 2015, seven companies’ proposals to work with ABPDU were funded; an additional five were funded in the program’s second year.

In round one of the SBV program, in fiscal year 2015, Lygos, a DOE Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI) spin-out founded in 2010, was awarded $300K to scale up its bio-malonic acid fermentation process at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and to validate process performance at the ABPDU.

“The process metrics we observed at lab scale were successfully transitioned to pilot scale at ABPDU,” said Lygos CEO Eric Steen. “It’s the first time malonic acid has been produced in meaningful quantities from renewable materials instead of petroleum.” In 2017 the company is planning to ship metric ton quantities of product.

Several companies that initially received the smaller project awards to work with ABPDU subsequently secured the larger voucher funding, noted Pray. In round two of the SBV program, HelioBioSys, Mango Materials, and Zymochem each received $200K to further develop projects.

And in the third round, in fiscal year 2017, new ABPDU partner Kalion received $200K to reach full manufacturing scale production of bio-based glucaric acid, one of the “Top Value Added Chemicals from Biomass” identified in a 2004 survey by staffers at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

“We had gotten to the point where we felt that if our process scaled successfully we would be able to commercialize it. But as a very small, lean company we needed another point of validation with our investors,” said Kalion President Darcy Prather. “Our work up to that point had been in two-liter shake flask or smaller. The timing worked perfectly so we were able to go from a two-liter to a 300-liter run via fermentation at the ABPDU.”

The relationship with the ABPDU has also been a great resource in helping Kalion connect with potential partners for the next level of scale up and commercialization, Prather added.

Another new collaborator, Bolt Threads, founded in 2015, is working with the ABPDU to investigate the biophysical characteristics of their engineered silk proteins and to refine methods for separating and purifying them. The proteins are produced in liquid form through a fermentation process with modified yeast, then wet-spun into fibers, which can be knit or woven into textiles.

“We were attracted to ABPDU because of their expertise, specialized equipment, flexibility, and ease of access,” said Ritu Bansal-Mutalik, Bolt Threads’ Principal Scientist for Recovery and Separations. “Their willingness to tailor projects to our needs has made them ideal partners. The scientific conclusions resulting from the partnership have accelerated our in-house research program, improving our timelines and providing real impact toward meeting our business objectives.”

Bolt Threads has begun transferring its lab-scale process into commercial-scale operations for three customers, including outdoor apparel maker Patagonia.

“Fermentation has become one of those technologies that has become vital in the 21st century economy, but there are almost no resources in the world to help small companies doing fermentation to develop their business,” said Ron Shigeta, Chief Science Officer for Indie Bio, a San Francisco-based biotech accelerator. “ABPDU is fulfilling a vital role in making that real.”

A number of startups that have participated in Indie Bio’s intensive four-month bench-to-product program have also collaborated with ABPDU. Recently Indie Bio formalized an umbrella agreement to get companies in its residency program off and running with ABPDU more quickly. “Speed is important to us,” Shigeta said, “and ABPDU has been very helpful to get companies further along toward economic viability.”