By Aliyah Kovner

Reliance on petroleum fuels and raging wildfires: Two separate, large-scale challenges that could be addressed by one scientific breakthrough.

Teams from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and Sandia National Laboratories have collaborated to develop a streamlined and efficient process for converting woody plant matter like forest overgrowth and agricultural waste – material that is currently burned either intentionally or unintentionally – into liquid biofuel. Their research was published recently in the journal ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering.

“According to a recent report, by 2050 there will be 38 million metric tons of dry woody biomass available each year, making it an exceptionally abundant carbon source for biofuel production,” said Carolina Barcelos, a senior process engineer at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Biofuels and Bioproducts Process Development Unit (ABPDU).

However, efforts to convert woody biomass to biofuel are typically hindered by the intrinsic properties of wood that make it very difficult to break down chemically, added ABPDU research scientist Eric Sundstrom. “Our two studies detail a low-cost conversion pathway for biomass sources that would otherwise be burned in the field or in slash piles, or increase the risk and severity of seasonal wildfires. We have the ability to transform these renewable carbon sources from air pollution and fire hazards into a sustainable fuel.”

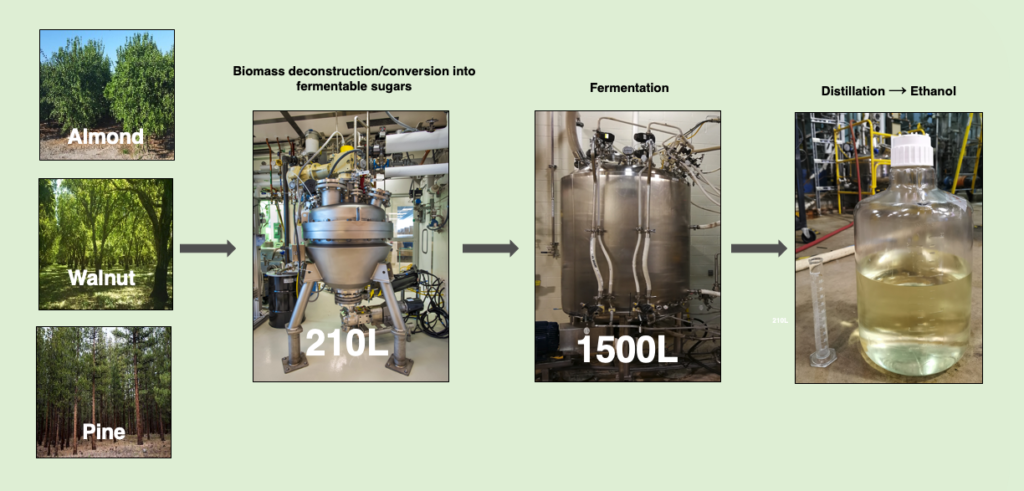

In a study led by Barcelos and Sundstrom, the scientists used non-toxic chemicals, commercially available enzymes, and a specially engineered strain of yeast to convert wood into ethanol in a single reactor, or “pot.” Furthermore, a subsequent technological and economic analysis helped the team identify the necessary improvements required to reach ethanol production at $3 per gasoline gallon equivalent (GGE) via this conversion pathway. The work is the first-ever end-to-end process for ethanol production from woody biomass featuring both high conversion efficiency and a simple one-pot configuration. (As any cook knows, one-pot recipes are always easier than those requiring multiple pots, and in this case, it also means lower water and energy usage.)

In a complementary study, led by John Gladden and Lalitendu Das at the Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI), a team fine-tuned the one-pot process so that it could convert California-based woody biomass – such as pine, almond, walnut, and fir tree debris – with the same level of efficiency as existing methods used to convert herbaceous biomass, even when the input is a mix of different wood types.

“Removing woody biomass from forests, like the overgrown pines of the Sierra, and from agricultural areas like the almond orchards of California’s Central Valley, we can address multiple problems at once: disastrous wildfires in fire-prone states, air pollution hazards from controlled burning of crop residues, and our dependence on fossil fuels,” said Das, a postdoctoral fellow at JBEI and Sandia. “On top of that, we would significantly reduce the amount of carbon added to the atmosphere and create new jobs in the bioenergy industry.”

Ethanol is already used as an emissions-reducing additive in conventional gasoline, typically constituting about 10% of the gas we pump into our cars and trucks. Some specialty vehicles are designed to operate on fuel with higher ethanol compositions of up to 83%. In addition, the ethanol generated from plant biomass can be used as an ingredient for making more complex diesel and jet fuels, which are helping to decarbonize the difficult-to-electrify aviation and freight sectors. Currently, the most common source of bio-based ethanol is corn kernels – a starchy material that is much easier to break down chemically, but requires land, water, and other resources to produce.

These studies indicate that woody biomass can be efficiently broken down and converted into advanced biofuels in an integrated process that is cost-competitive with starch-based corn ethanol. These technologies can also be used to produce “drop-in” biofuels that are chemically identical to compounds already present in gasoline and diesel.

The next steps in this effort is to develop, design, and deploy the technology at the pilot scale, which is defined as a process that converts one ton of biomass per day. The Berkeley Lab teams are working with Aemetis, an advanced renewable fuels and biochemicals company based in the Bay Area, to commercialize the technology and launch it at larger scales once the pilot phase is complete.

This research was supported by the California Energy Commission and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science. JBEI is a DOE Bioenergy Research Center dedicated to developing advanced biofuels. The ABPDU, funded by the DOE Bioenergy Technologies Office, is a Berkeley Lab-led facility that works with industry, academia, and other national laboratories to develop and optimize bio-based processes for producing chemicals, materials, and fuels.